Children in the UNCRC

On the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, how they conceptualise kids, and the childhood theories that those conceptualisations reflect.

In today’s instalment of Grown-ish, we’re diving into a brief, theoretical analysis of the United Nations Conventions on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), established back in 1989. Since there’s lots to unpack, we’re dipping our toes in today by looking at how the UNCRC actually sees the child, and how this can be further explained using our favourite theories of childhood.

The UNCRC? I don’t know her…

Thinking about the UNCRC is pertinent to the discussion of children’s rights, because it stands to be the most comprehensive and internationally recognised body of statements regarding this topic to date. The document defines a child as “every human being below the age of 18 years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier” (UN General Assembly, 1989, p. 4). Its 54 articles aim to protect children from violence, neglect, abuse and exploitation in all forms and from all institutions, and also considers the protective needs of children with disability, special needs and lack of a family environment. Because of its attentiveness to lots of holistic and nuanced issues, the UNCRC has been regarded as a comprehensive legislative document with significant implications for childhood experiences on a global scale. But, despite being ratified in all UN states besides the US1, the UNCRC has been subject to lots of controversy about whether it’s actually being implemented effectively or not - more on this another day.

The UNCRC and Theories of Childhood

The UNCRC mirrors a shift in the collective philosophy of childhood from a modern Western perspective, steering away from a solely protective standpoint to one more embedded with ideas of moral and legal rights (Holzscheiter, 2020, p. 1616). Based on this positioning, we’re going to take a look at the theoretical images of childhood that are reflected in the articles of the UNCRC.

From this, we see that the UNCRC positions the child using a duality of thought. The kid is an innocent being in need of protection, but they’re also an entity working towards independence and garnering social, economic and political capabilities in adulthood. The former aligns with the image of the child as an innocent2, and the latter with the idea of the child as an adult-in-training.

i. The Innocent Child

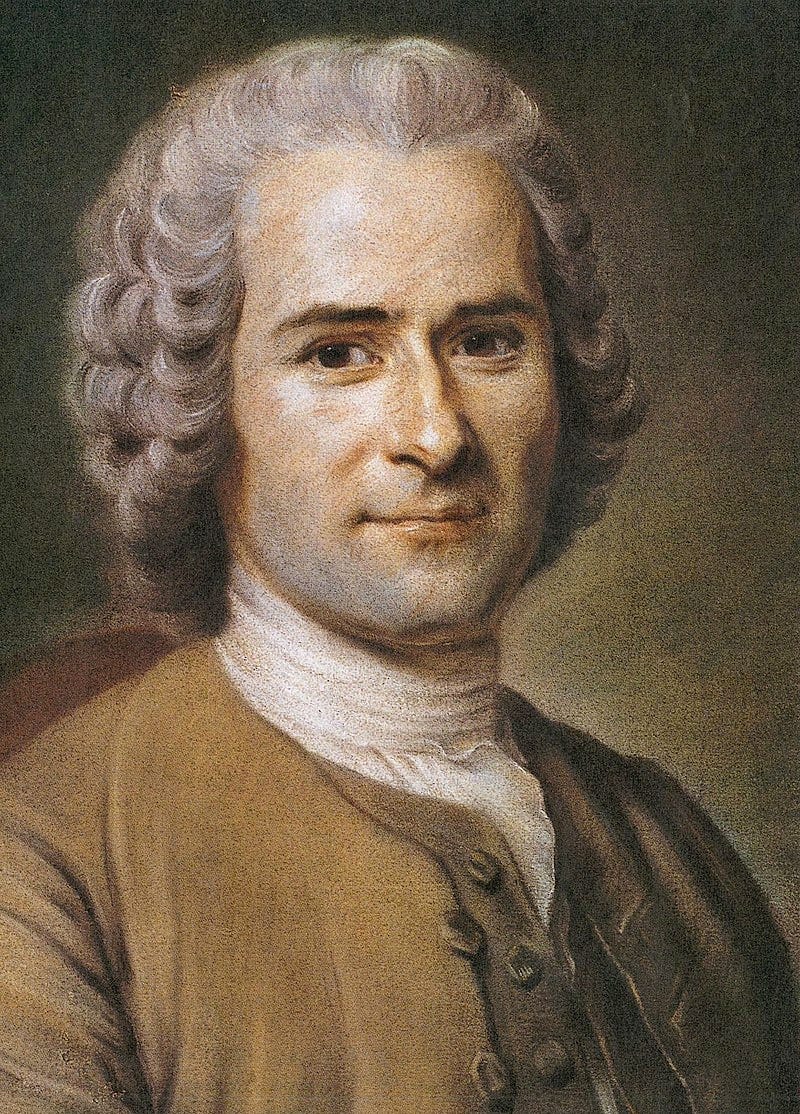

Perceptions of childhood expressed in the UNCRC seem to align with the image of the child as an innocent. Our main man Rousseau is famously credited with the conceptualisation of the child as a “moral innocent… standardly corrupted by social convention (Archard, 2014, p. 34). Here, innocence is the absence of guilt and sin (no experience = no wrongdoing), both of which are basically underpin the understanding of childhood in modern Western culture. Based on these ideas of purity, weakness and lack of knowledge, A more nurturing, child-centric approach to child-rearing emerged as a response to these ideas of purity, weakness and naiveness. This approach is a long-lasting descendant of Rousseau’s work, seeing as he emphasised the need to “preserve the innate goodness of the child… [and] a commitment on part of adults to protect children from harm” (Garlen, 2020, p. 970). This is reflected, for example, in Articles 19, 34 and 39 of the convention, which call for the protection of the child from “all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse”, all sexual exploitation as well as recovery from any such experiences (UN General Assembly, 1989, p. 7-11). The UNCRC’s depiction of children as vulnerable and incompetent also means that childhood is viewed as a preparatory stage for adult life. So, the view of the child as an innocent links closely with the idea of the child as an adult-in-training…

ii. The Adult-in-Training

Conceptualisations of ideal and real childhoods in the UNCRC also depict the child as an “adult-in-training… working through various motor, psychological and social tasks, or stages, to reach adulthood” (Sorin & Galloway, 2006, p. 17). Lots of developmental psychologists, life Piaget and Freud, perceived of the child as a ‘human becoming’ instead of a ‘human being’3. So, the power of the adult is in their ability to be an effective facilitator, and to harness the child’s capabilities and whip them into shape in a way that lines up the social norms and values of the current context. Since the adult is responsible for all of that, it stands to reason that they’re also more knowledgeable than the child, who is an apprentice to their mentor4. Articles 28 and 29 of the UNCRC allude to these ideas - the former calls for equal access to education – including primary, secondary, higher and/or vocational education – for all children, and the latter highlights the outcomes that an education should seek to achieve (UN General Assembly, 1989, p. 9). These outcomes include fostering the child’s “abilities to their fullest potential… [as well as] preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society” (UN General Assembly, 1989, p. 9). Making education compulsory a tool which prepares and equips young people for adulthood inherently proves that the conceptualisations of childhood in the UNCRC reflect the image of the child as an adult-in-training.

And that’s it for today, folks! In this instalment of Grown-ish, we talked about the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). We start off with a brief overview of the document, then moved on to discuss how they conceptualise children - and therefore, how they represent them. This is important because, the way that a globally-referenced document perceives of the child will shape how a lot of people think about what childhood should be. Based on the images of the child as the innocent and the adult-in-training, we made sense of the UNCRC’s conceptualisation of children through theory and practice. Do you think that the UNCRC offers a holistic and representative view of the child? Personally, I think their minority world focus is a bit exclusionary, and doesn’t account for many cultures which have different ways of articulating and measuring children’s rights. Do you agree? Let me know in the comments!

If you’ve enjoyed this read, go ahead and subscribe to join me on this journey of the exploration of childhood and youth studies.

Until next time!

Signing off,

Grown-ish.

But like… why?

Sweetheart Rousseau is back in the mix!!! We love to see it.

Rude.

Their royal subjects, as it were.

References:

Archard, D. (2014). The Concept of Childhood. In Children: Rights and childhood (pp. 19-41). Routledge.

Garlen, J. C. (2020). Innocence. In D. T. Cook (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood Studies (pp. 968-971). SAGE Publications.

Holzscheiter, A. (2020). United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). In D. T. Cook (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood Studies (pp. 1615-1621). SAGE Publications.

Sorin, R., & Galloway, G. (2006). Constructs of childhood: Constructs of self. Children Australia, 31(2), 12-21.

UN General Assembly. (1989). The Convention on the Rights of the Child. https://www.unicef.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights/